About Bhikkhu Moneyya

Over the years, Bhikkhu Moneyya has proven himself to be a man for all seasons – homeboy and world traveler, student and dropout, peacenik and rebel, businessman and poet, husband and celibate monk, skeptic and lover of truth. Born in 1946, he dropped out of university in his second year and spent the next three years traveling through the Middle East and Europe, experiencing life from a different perspective and gaining in that process a critical view of the American dream and politics in general. He became a Buddhist in 1968 and took higher ordination in Myanmar as a Theravada monk in 2002. Bhikkhu Moneyya currently lives in Bali, practices yoga and meditation and enjoys swimming, walking, vegetarian food and the natural beauty of the island. As a monk, his greatest wish is for world peace, the cessation of greed, hatred and delusion and the happiness of all.

LiFT: Tell us about your book, the journey of writing it and its content.

Bhikkhu: “The Moneyya Chronicles is a compilation of poetry and prose, consisting of more than sixty poems and 200 musings of varying length and subject matter. The book begins shortly before my conversion to Buddhism in 1968 and reflects my journey over the past 55 years, through a marriage and two businesses, my ordination in Myanmar in 2002 and my twenty-plus years as a Theravada Buddhist monk, up through the composition of my most recent poem in December of 2022. Naturally, the book highlights a number of traditional and contemporary Buddhist themes, but it also reflects issues that arose as a natural consequence of the times. For me, as an American born shortly after the end of the Second World War, one of the issues that has only grown stronger over time is a basic mistrust of the US government, coupled with a loss of faith in the “American Dream” and politics in general.

This erosion of confidence in a country that many people around the world still look up to as a pillar of Democracy had its origin in the following events: the assassination of JFK (and its subsequent coverup), my parents’ failed marriage, the Vietnam War, life in Israel and my growing disillusionment with Zionism, and the fundamental hypocrisy of society’s recent leaders. And yet, just as the Buddha’s teachings begin with an understanding of the universality of suffering and then proceed to its cause and finally arrive at the cessation of that suffering, so my book has grown, page by page, to encompass a far wider purview of subject matter than mere cynicism and scepticism would allow.

The poems and musings are arranged in chronological order to make it easier for the reader to trace my journey through the various stages of development in my life as a Buddhist practitioner and writer. Several of the earlier poems are actual translations from the original Pāli, a script based on the language spoken by the Buddha some 2600 years ago. A few merge my Buddhist orientation with those of other spiritual traditions, primarily Christianity and Hinduism. “Tears of Blood,” for example, has an unmistakably Christian theme, while “Hansīka” and “Return” were written during my residence at a yoga ashram. A turning point occurred in 2015, during my stay at a Christian spiritualist church in the Philippines, where I wrote “If you want to be a Christian” – a poem focusing on the highly publicised shooting of Clementa C. Pinckney and eight fellow Afro-Americans during a church service in South Carolina – and “The Right Mishmash” – a poem where Christianity and Buddhism meld together in a rather unique way. Another slightly later but no less significant poem, “Humility,” merges my Buddhist perspective with a Christian-style contemplation on the virtue of humility.

As early as 2012, my poems began to grow more diversified in their style and subject matter. For example, “Beeing Time” and “Tree Ode” focus on a bee and tree, while “Lord of the Ring” and “Manny” use the boxing/MMA ring as a metaphor for life, and “Lady,” “The First Hundred Days,” “Ode to Bernie Sanders” and “True Greatness” are poems about contemporary political figures. Three notable examples of diversification in style are seen in “Whitman’s Dream,” which relies heavily on metaphor and symbolism, “The Right Mishmash,” which incorporates a stream-of-consciousness writing style, and “Kathina in Sri Lanka,” which was written in prose-like free verse, to chronicle my stay at a Theravada monastery in Sri Lanka, during the Buddhist celebration of Kathina.

Since 2015, Bali has been my primary residence. During this time, I have gotten to know many Balinese and come to appreciate their gentle character and friendly manner, so when the COVID lockdowns began in March of 2019, it was not difficult for me to sense a gradual shift in the mood of its people. Initially, they were enthusiastic and supportive; as the lockdowns continued, however, and were coupled with other equally draconian measures, including police checkpoints along the roads, fines for not wearing a mask and increasingly oppressive vaccine mandates, the island’s friendly and relaxed atmosphere gradually gave way to a climate of fear and mistrust.

I began to feel a rising cynicism about the constant paranoia and hype that was being fed to us by the major news media in what seemed like a psychological operation to me – under my breath, I called it “the 9/11 of the pharmaceutical industry.” After two-plus years of lockdowns, these feelings finally coalesced into the verses of my poem “The Jabberblog” (a parody of Lewis Carroll’s famous children’s poem, “Jabberwocky”). The poem was a satire of the ongoing pandemic, and its purpose was to expose the dangers of blindly accepting the policies of some autocratic governmental agency or one of its officials. Nevertheless, as serious as this may sound, “The Jabberblog” is a fun poem to read, and, for that, I owe a debt of gratitude to Lewis Carroll.

My two final poems, “Gay Parade” and “A Christmas Carol,” like “The Jabberblog” pursue a line of questioning that is not afraid to hold society’s current-day tenets to the most rigorous standards of truthfulness and morality. “Gay Parade” begins with a comparison between the LGBTQIA movements in Indonesia and the West, and then generalizes to a comparison between the two cultures, while “A Christmas Carol” examines the dual concepts of technocracy and transhumanism from the perspective of karma and rebirth. Of course, these are not the only poems that I have written over the past two years, but because they represent such a radical shift from my Buddhist-genre poems, I felt it was important to mention them.

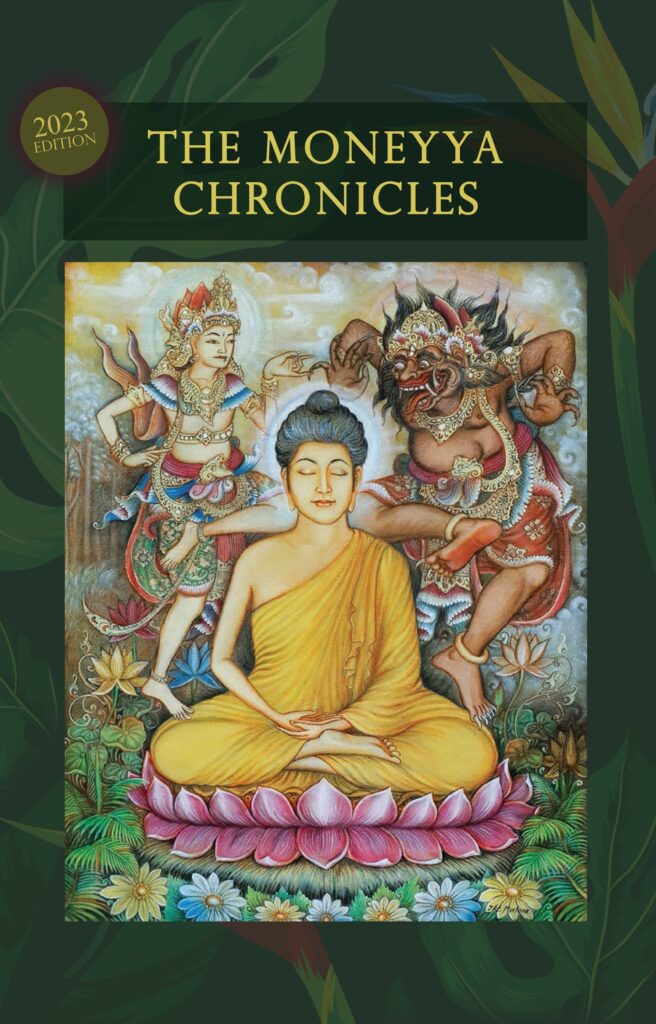

My poems are followed by a postscript of aphorisms and musings, which I have separated out from the main body of the poetry due to their difference in size and character. Anyway, because the subject matter of these musings is so vast and varied, I’m not going to try to describe or categorize them at this point. Suffice it to say that what I like about aphorisms and musings is that most of them are short and pithy, so it’s possible to say a lot in a few words, plus the writer isn’t encumbered by trying to stick with a particular writing style. One of the main things that makes this book stand out is the artwork. With the varying styles of as many as nine different artists and eighteen individual paintings to complement the poems, reading the book takes on a whole new dimension of visual richness. My search through the sea of Balinese artists and having the opportunity to work with them was a really fun part of producing the book for me. In particular, I would like to thank I Ketut Murtana for the intricate beauty of his traditional Balinese paintings, several of which he made at my request, Chas “ginty” Spencer, who also made paintings for me at my request, and Ni Komang Atmi Kristiadewi for the happiness and childlike celebration of nature that her painting style conveys. All three happen to be personal friends, as well as talented artists.

LiFT: Why you chose this title?

Bhikkhu: When I ordained as a Theravada monk, I was given the name “Bhikkhu Moneyya.” “Bhikkhu” means “monk” in Pāli, and “Moneyya” means “silent sage.” That’s how my book got its name – since its poems and musings chronicle the life of Bhikkhu Moneyya.

LiFT: When did you realize that you want to be a writer and what’s your inspiration behind it?

Bhikkhu: I enjoyed writing poetry even as a child, and although my primary goal in life was never to become a “poet” or “writer,” I felt I had a message to share and that is what motivated me to continue writing – it was something that grew organically as a form of self-expression.

LiFT: Where do you see yourself ten years down the line in the world of literature?

Bhikkhu: To be honest, I never really thought about that before. Of course, everybody wants to be remembered for having made some significant contribution in the field of their endeavour, but in my waning years, I prefer to leave that task to posterity.

LiFT: How much do you think marketing or quality of a book is necessary to promote a particular book and increase its readers?

Bhikkhu: Of course, marketing and quality are always important. In the past, because I liked to share what I had written with others, my books always ended up producing a negative profit margin. Now that I am working with a professional publisher (Damick Publications), I am looking forward to accessing new markets and techniques for getting the word (and book) out. Will see how it goes . . .

LiFT: What is the message you want to spread among folks with your writings?

Bhikkhu: Always seek the truth, within and without. It is the quality of your character that will ultimately determine the direction of your life. If your heart is pure, you will be able to die in peace when the time comes.

LiFT: What do you do apart from writing?

Bhikkhu: Practice yoga and meditation, swim, walk and enjoy the beauty of Bali.

LiFT: What are the activities you resort to when you face a writer’s block?

Bhikkhu: I find that increasing meditation or doing a short meditation retreat can help to clear the mind and get inspired again.

LiFT: Are you working on your next book? If yes, please tell us something about it.

Bhikkhu: Not at the present time.

LiFT: What are your suggestions to the budding writers/poets so that they could improve their writing skills?

Bhikkhu: Make friends with those who have a common interest in writing. Maybe join a writing class or poetry group. Don’t spend too much time on the internet.

LiFT: Anything Else that you would like to share with the readers?

Bhikkhu: Be happy. Share whatever you have with others. Read something that inspires you. Do something that inspires you. Enjoy the beauty of nature. Make some good karma.

Click here to order Bhikkhu Moneyya’s Book – The Moneyya Chronicles